What is Git

The major difference between Git and other VCS (Version Control System) is the way Git thinks about its data. Conceptually, most other systems store information as a list of file-based changes. These other systems think of the information they store as a set of files and the changes made to each file over time. Git dosen’t think of or store its data this way, instead, Git thinks of its data more like a series of snapshots of a miniature filesystem. With Git, every time you commit, or save the state of your project, Git basically takes a picture of what all your files look like at that moment and stores a reference to that snapshot. To be efficient, if files have not changed, Git dosen’t store the file again, just a link to the previous identical file it has already stored. Git thinks about its data more like a stream of snapshots. Because you have the entire history of the project tight there on your local disk, most operations seem almost instantaneous, and most operations in Git need only local files and resources to operate — generally no information is needed from another computer on your network.

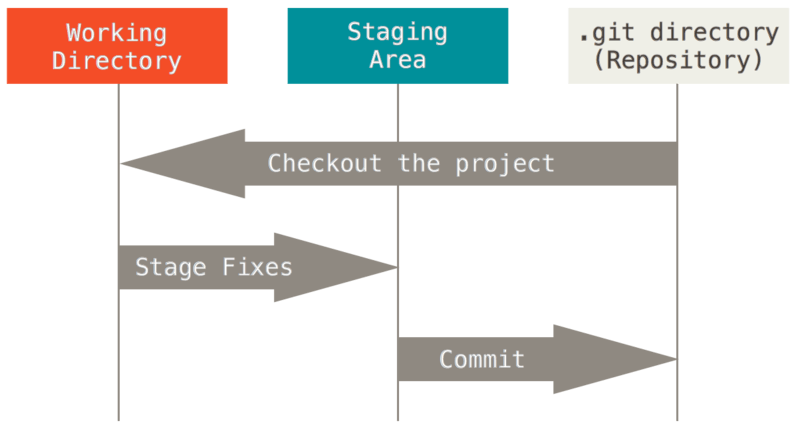

Git has three main states that your files can reside in:

- modified: you have changed the file but have not commited it to your database yet.

- staged: you have marked a modified file in its current version to go into your next commit snapshot.

- committed: the data is safely stored in your local database.

This leads us to the three main sections of a Git project:

- the working directory: a single checkout of one version of the project. These files are pulled out of the compressed database in the Git directory and placed on disk for you to use or modify.

- the staging area: a file, generally contained in your Git directory, that stores information about what will go into your next commit. Its technical name in Git parlance is the “index”, but the phrase “staging area” works just so well.

- the Git directory: stores the metadata and project database for your project. This is the most important part of Git, and it is what is copied when you

clonea repository from another computer.

Git comes with a tool called git config that lets you get and set configuration variables that control all aspects of how Git looks and operates. These variables can be stored in three different places:

/etc/gitconfigfile: Contains value applied to every user on the system and all their repositories. If you pass the option--systemtogit config, it reads and writes from this file specifically.~/.gitconfigor~/.config/git/configfile: Values specific personally to you, the user. You can make Git read and write to this file specifically by passing the--globaloption, and this affects all of the repositories you work with on your system.configfile in the Git directory of whatever repository you’re currently using: Specific to that single repository. You can force Git to read from and write to this file with the--localoption, but that is in fact the default

Getting a Git Repository

You can take a local directory that is currently not under version control, and turn it into a Git repository.

1 | $ cd /Users/user/my_project |

Or, you can clone an existing Git repository from elsewhere.

1 | $ git clone <url> [target-directory] |

Recording Changes to the Repository

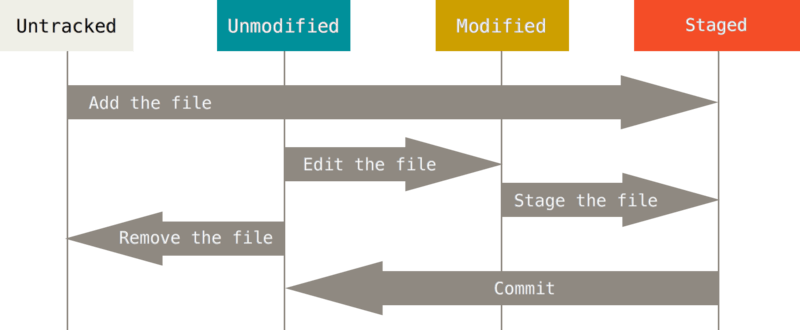

Each file in your working directory can be in one of two states:

- tracked: Tracked files are files that were in the last snapshot or in the Staging Area. In short, tracked files are files that Git knows about.

- untracked: Any files in your working directory that were not in your last snapshot and are not in your staging area. When you first clone a repository, all of your files will be tracked and unmodified because Git just checked them out and you haven’t edited anything.

1 | # determine which files are in which state |

Often, you’ll have a class of files that you don’t want Git to automatically add or even show you as being untracked. In such cases, you can create a file listing patterns to match them named .gitignore

The rules for the patterns you can put in the gitignore file are as follows:

- Blank lines or lines starting with

#are ignored. - Standard glob patterns work, and will be applied recursively throughout the entire working directory.

- You can start patterns with a forward slash (

/) to avoid recursivity. - You can end patterns with a forward slash (

/) to specify a directory. - you can negate a pattern by starting it with an exclamation point (

!).

Here is an example .gitignore file:

1 | # ignore all .a files |

Working with Remotes

Remote repositories are versions of your project that are hosted on the Internet or network somewhere.

1 | # show the list of the shortnames of each remote handle you've specified |

Tagging

1 | # list the existing tags |